|

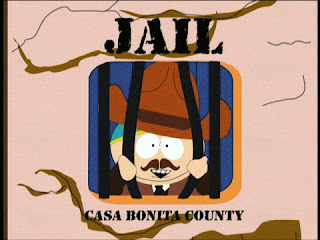

| The Notorious B.I.G. (left) & 2Pac (right) |

I've got this weird dream of one day making an epic biopic.

For those of you who don't read movie reviews regularly, a biopic is a "biographical picture," a film that traces the life of a historical or cultural figure, usually from childhood to death. The most obvious recent examples are films like Ali, Ray, Walk the Line ("Ray for white people." - Jon Stewart), and the new Clint Eastwood film J. Edgar.

This dream of mine is weird for one reason: biopics suck.

As pretty much anyone could tell you, mainstream movies are typically structured and written based on a three-act structure. At the end of the first act, after the filmmakers have finished establishing the world and its characters, this thing happens called the "inciting incident." The inciting incident is almost always supposed to shock the characters in a bad way, shake up their world, and set the plot mechanics into motion. The second act climaxes as the character/s reach their lowest point emotionally. They manage to overcome the obstacle and the various plot threads are tied up and taken care of in the third act. Look at any movie that gets a wide release. It follows this formula.

In a way, the three-act structure rule is the American version of Aristotle's Poetics: it describes the most logical, efficient, and emotionally satisfying method for structuring a narrative. The problem comes in when, as a writer or a viewer, you're forced to recognize the fact that genuine human experiences typically don't fit into a three-part progression of events. This isn't so much a problem when you're working with characters who in no way resemble real human beings (almost every romantic comedy), but when you're taking on a biography, a real historical figure whose actual life story we all have access to, the three-act structure becomes tyrannical and ridiculous.

In my mind, the best example of this problem -- filmmakers stuffing a complex life story into a standard three-act narrative -- comes in the biopic of The Notorious B.I.G., a film called Notorious that strangely and deliberately avoided addressing all of the most notorious aspects of the life of the criminal poet Biggie Smalls.

Although this blog probably doesn't suggest it, I do have other interests outside of the cinema, and music happens to be one of them. I search for and listen to music constantly, but as with films, my tastes are a little strange. Where I come from, most everybody listens to Dave Matthews Band, O.A.R., Dispatch, preppy jam band shit like that. That's fine, it makes sense, it's New Hampshire. But around the time I started caring about music, starting understanding its effects, is the same time that my skinny white friend Zig introduced me to hip-hop.

The Notorious B.I.G.'s first album, Ready to Die, was the first rap album I ever bought. It's a classic, genre-defining concept album that traces Biggie's life from birth, to his life on the streets robbing and killing, to his imagined death by suicide on a track called "Suicidal Thoughts." This is the song with which Smalls ended the only album he released in his short life (he was killed in L.A. at age 24):

When I die, fuck it I wanna go to hell,

Cause I'm a piece of shit, it ain't hard to fuckin' tell,

It don't make sense, goin' to heaven wit the goodie-goodies

Dressed in white, I like black Tims and black hoodies...

Crime after crime, from drugs to extortion

I know my mother wished she got a fuckin' abortion.

He goes on to theorize that the "people at the funeral frontin' like they miss me," that the mother of his child is glad he's gone, that he's reached his peak and can't speak. And then he shoots himself in the head and the album ends.

This is a particularly bleak and brutal way to end a narrative, and I believe it speaks to the persona that Biggie spent his last few years of life cultivating. The simpler rhymes I just quoted in "Suicidal Thoughts" don't totally do his art, but Biggie is unquestionably a rapper of the highest order, one of the most charismatic and naturally gifted wordsmiths to be found in popular American music. However, when you listen to Ready to Die, and especially "Suicidal Thoughts" or "Gimme the Loot" or "Machine Gun Funk," you have to come to terms with something pretty basic: Biggie Smalls was mean.

The final act of Notorious posits that Biggie spent his last day on Earth reconciling with the mother of his first child, telling his own mother that he's proud of her, making heartfelt requests that his children join him in California, and apologizing to Lil Kim for all the times he treated her badly. It's a cheesy movie with a worse final act that commits every narrative cliche available to it, and that's a damn shame. Biggie Smalls might not have been a nice guy, but he was a brilliant artist. He deserved better.

Any fan of Ray Charles or Johnny Cash could accuse their respective biopics, the aforementioned Ray and Walk the Line, of the exact same problem. They're films filled with cliches that reduce complex and rebellious artists to these moral automatons teaching us all lessons about why you should be nice to people and why family is important. You don't need cliches to express those idea. And besides, those ideas don't do justice to the aesthetics and the bodies of work that these artists crafted.

My weird dreams is to make a biopic that doesn't reduce the central figure to a moral puppet, one that respects and pays homage to that figure's specific persona and life philosophy. It's not hard to make a three-act film that ties up all its own loose ends along with all of its protagonist's flaws. The hard part is making an emotionally satisfying film that recognizes its protagonist's complicated humanity. After all, the evil inside defines us as much as the good.